| Panel Discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Slide 1 (Brown)]

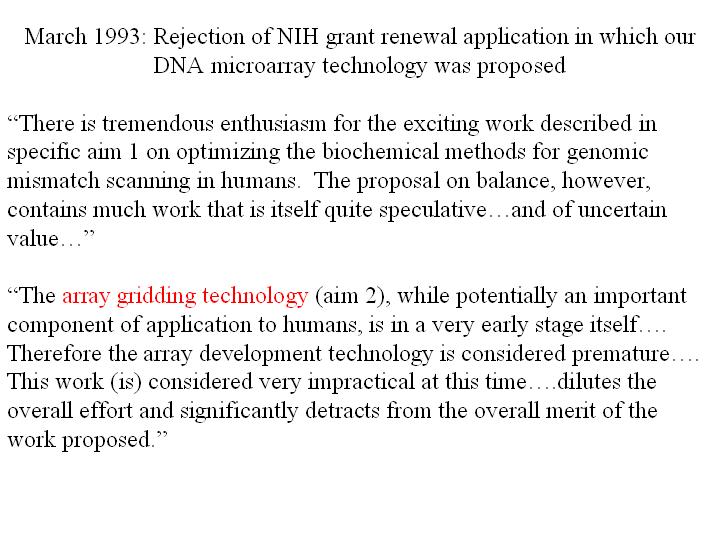

[Slide 2 (Brown)]

[Slide 3 (Brown)]

|

Nishimura:

Thank you very much Amano-san. Nakamura-san, please give your talk.

Nakamura:

My name is Nakamura. I plan to talk without slides. As Amano-san said, in the case of blue light emitting diode "knowledge" was the problem - "entrepreneurship" could create a large market if the product could be developed. One other big point concerning "knowledge" that Amano-san did not mention, but which applied to my case, was the idea of good and bad luck. For example, there were two candidate materials in the development of the blue light emitting diode. They were Zinc-selenium (ZnSe) and Gallium-nitride (GaN). I started my research in 1989, and at that time almost all researchers had selected ZnSe. Very few researchers had selected GaN. A tremendous number of first-class researchers were trying to use ZnSe. They did eventually develop a device similar to the blue light emitting diode but its lifespan was very short. It was just unlucky. The intellectual effort they expended represented a tremendous amount of intellectual energy. The small number of researchers working on GaN meant that the amount intellectual energy being applied was also small. Put simply, this is just a matter of good and bad luck. If the same number of researchers trying ZnSe had tried GaN, the blue light emitting diode would have been realized at an earlier date. The selection of the material was a matter of luck. If you were following common sense, you naturally selected ZnSe. Great "knowledge" is created when you try things against common sense. It was against common sense to select GaN at that time, but by choosing to go against common sense there was also the opportunity to create a great leap in "knowledge."

I will mention one more thing that Amano-san and Akasaki-san did not mentioned. Many markets were created by the invention of blue light emitting diode. There is one unique problem in those markets in Japan, which I want to talk. Even though a very good product might have been developed, the high level of regulation in Japan prevents people from choosing to adopt it. One typical example is traffic signals. Those of you who travel abroad will be surprised to find LED traffic signal used everywhere in the world except Japan. If you install LED traffic signals, electrical power consumption is reduced to one tenth, and the lifespan of the lamp become almost infinite. So when you use LED traffic signals energy savings and resource savings can be realized. Everywhere in the world is changing over to this technology, except Japan. Only in Japan can you not see green LED traffic signals. Yet this technology was invented in Japan. When you ask why they the technology is not being used, the answer is that, as you know, there are five traffic signal companies in Japan who monopolize this market. They are staffed by retired "Amakudari, descent from heaven" bureaucrats from the police department. LED traffic signals need no maintenance because, unlike incandescent lamps, there are no breakages. The existing traffic signal companies make their profit through maintenance fees, and so they do not want to change to LED traffic signal because maintenance fees will fall to zero. Therefore, by failing to create a system to popularize a technology of such value to society, you are actively creating a system that prevents people from using that technology. With that comment I will conclude my talk.

Nishimura:

Brown-san, please give your talk.

Brown:

My name is Patrick Brown. I think one of the fundamental facts about new inventions and new discoveries - new progress in engineering and technology - is that it always comes from building on knowledge and discoveries and ideas from other people, previous generations of scientists, and scientific colleagues. And on the other hand, when discoveriesc new ideas are developed and discoveries are made, very commonly the people who make and report those discoveries haven't fully appreciated their potential. It's certainly true in every scientific paper that I've ever published - every time I've published any data there have been other people who have recognized potential or things in the work that we've done that I wasn't smart enough to recognize myself. So an absolutely essential feature of scientific progress and discovery is the sharing of information and knowledge within the scientific community, and spreading that knowledge also to the whole world so that as many people as possible can have the potential to build on existing knowledge.

So what I'd like to talk about briefly is the new possibilities that the development and spread of the Internet has opened up for a fundamental change in the way that scientists share their ideas and discoveries with each other and with the public. The ability to make a tremendous amount of information instantly available - essentially for free - to anyone in the world who has access to the Internet, has I think a tremendous potential for bringing the benefits of science research and discovery to anyone who might want to use them. To allow scientists, engineers and business people to have essentially complete access to all the work that has preceded them so that they can use their own creative ideas to build on that. And also to make that information available to people who aren't scientists - just, for example, high school students who are just curious and interested in learning what's new in science, learning about the latest engineering developments, and so forth.

Most of the world's scientific research, scientific knowledge, is not propriety - its not protected intellectual property, and it's not classified - it's not secret. The scientists who produce it, or the engineers who develop it, are perfectly willing to publish that freely. But the problem is that almost none of that information - even though the people who generate that knowledge are willing to share it with anyonec they give it away, they don't get any revenue from publishing their discoveries - it's not available to other scientists to other scientists and engineers. Not freely available - it's only available primarily to wealthy institutions who can afford to pay the subscription costs for scientific and technical publications and that's because the traditional publication mechanism - which developed in the era when scientific information was shared by printing it on paper and delivering it in trucks - the traditional mechanisms depended on giving the copyright to the publishers, and then of course the publishers, to be profitable, had to limit access to the published work. They couldn't afford to give it away. Well that business model isc I don't think the right business model any more - it's not the best for society, it's not the most economically efficient.

Scientific ideas and discoveries from research they're not like commercial products. The cost a lot to produce -. all the investment that governments and companies make in research and discovery: In the United States alone just the government investment in basic, non-classified, non-proprietary research is more than $40 billion a year - about 5 Trillion Yen a year. And the purpose of that research is just to generate useful new knowledge for the public good. It costs a lot to produce the knowledge but the scientists are willing to give it away and the funders are willing to give it away, and the information is a unique kind of raw material. It's essentially infinitely renewable and it's also almost infinitely cheap to distribute over the Internet. So the question is why should this knowledge only be accessible to the scientists in wealthy institutions in wealthy countries. And even for those scientists - even at Stanford which has as about as much access to information as anyone - much of that information is very poorly accessible. It's very hard to search the entire body of published scientific research.

Well I don't think this situation is necessary. I think in fact that scientists and public agencies and companies that support most of the scientific research in the world, as well as the public - the citizens who pay for it with their tax dollars - should demand that the work that they've done or supported financially should be published in a way that makes it freely available online to anyone in the world. If everybody agrees to that system, everyone will benefit from it by having greater access to the information. And I think that there are very practical business models for publication in that way that can be developed and I'm actually involved in working on that right now. One of the most important steps - just to conclude - that we can take improve productivity - scientific productivity, engineering productivity, productivity in terms of medical care, even in terms of business productivity - would be to make the world's scientific and medical and engineering knowledge, that's non-proprietary and non-classified, available on an online public library. It actually wouldn't even be that expensive and I think this would be a great step for promoting techno-entrepreneurship, as Dr Takeda says, and we should all try to promote it. That's all thank you.

|

|

|